As noted before, Major League Wrestling’s original antitrust lawsuit against WWE was dismissed this past February and had filed a new amended lawsuit this past March.

PWInsider’s Mike Johnson reported that the presiding judge, Edward J. Davila, of the United States District Court, Northern Division of California, San Jose had denied WWE’s motion request to have MLW’s amended lawsuit dismissed on Thursday based on recent court documents.

In his ruling, Davila rejected several of WWE’s claims in their motion to have the lawsuit dismissed and found that WWE had presented enough sufficient evidence for their claims of WWE acting as a monopolistic power.

Davila’s ruling revolved around MLW’s claims that WWE had violated the Sherman Act and focused on the parts of the act that pertained to this lawsuit.

In regards to his rejection of WWE’s motion, Davila stated in his ruling:

“MLW alleges a relevant product market defined as “the sale or licensing of media rights for professional wrestling programming” and a relevant geographic market of the United States. The relevant market “includes the media rights for professional wrestling TV series and programs that are aired on U.S. national television networks, U.S. cable and satellite television networks, pay-per-views purchased by U.S. households, and U.S. streaming services.”

WWE argues that the [First Amended Complaint] does not sufficiently allege that purchasers of the relevant product—i.e., television networks and streaming services—have no reasonably interchangeable content alternatives to wrestling programming. WWE contends that the small fraction of media platforms that air professional wrestling content, as alleged in the FAC, “confirms that [the majority of platforms] view other content as reasonable alternatives for professional wrestling.”

Additionally, WWE posits that “to define a relevant market, MLW must plausibly allege that men aged 35-44 only watch professional wrestling, and thus networks and streaming services must purchase professional wrestling content in order to attract those viewers. MLW does not and could never allege this.”

The Court disagrees. Although the professional wrestling media rights market may be narrow, the Court may reasonably infer from the FAC’s allegations that other forms of programming content are not economic substitutes for professional wrestling. Importantly, MLW defines its relevant market by explicitly distinguishing it from reasonably interchangeable substitutes. Cf. Tanaka, 252 F.3d at 1063–64 (finding complaint failed to define relevant market where allegations regarding product market did not discuss interchangeability with any specificity). For example, the FAC alleges that professional wrestling programming is a niche market segment that is distinct from comedy, drama, reality, news, or sports shows.

The FAC further alleges that the professional wrestling audience is demographically distinct from the general audience for prescheduled television shows in that it skews male and toward the 35 to 44 age range, as opposed to female and toward the over-60 age range.

Based on the above allegations, it is not “apparent from the face of the complaint that the alleged market suffers a fatal legal defect.” Newcal, 513 F.3d at 1045. Here, Plaintiff’s allegations regarding the relevant product market are sufficiently detailed to survive a motion to dismiss. See Sidibe v. Sutter Health, 667 F. App’x 641, 642–43 (9th Cir. 2016) (finding dismissal of antitrust action based on market definition inappropriate where allegations were “sufficiently detailed”).

Defendant’s cursory challenge to Plaintiff’s alleged relevant geographic market of the United States also fails. Defendant suggests that Plaintiff was required to allege “fact[s] suggesting the market for media rights is limited to the United States and is not, instead, a [U.S.] and Canadian market or a global market.” Id. As the Ninth Circuit has noted, “the ‘relevant market’ is typically a factual element rather than a legal element,” and alleged markets may therefore “survive scrutiny under Rule 12(b)(6) subject to factual testing by summary judgment or trial.” Newcal, 513 F.3d at 1045 (citation omitted). And although Plaintiff is not required at this stage to plead specific facts eliminating all other possible markets as the relevant geographic market, the Court notes that the FAC’s allegations do support the claimed market. See, e.g., FAC ¶ 68 (alleging that Fox and NBC operate the two cable networks with the largest coverage in the United States), (“WWE reached a five-year agreement with NBCUniversal’s streaming platform, Peacock, for the exclusive streaming rights of WWE programming in the United States.”). Accordingly, the Court finds that Plaintiff had adequately alleged relevant product and geographic markets.”

In regards to his support of MLW’s antitrust claims, Davila stated in his ruling:

“The Court finds that MLW has sufficiently pleaded circumstantial evidence of WWE’s monopoly power. The FAC alleges that WWE captures 92% of the revenue generated by the sale of media rights for professional wrestling programming. Defendant argues that MLW must allege facts explaining why revenue share is an appropriate measurement of market share, but cites only to cases that evaluated the proper market share metric based on factual findings.

At the pleading stage, MLW’s allegations of the revenues generated from the sale of professional wrestling media rights, and WWE’s 92% share of that revenue (with the next largest competitor possessing a 6% share) are sufficient to show dominance in the market.

In addition to defining the relevant market and alleging WWE’s dominance in that market, MLW has also sufficiently alleged barriers to entry, as required to show circumstantial evidence of market power. Plaintiff alleges that WWE has used its dominant stature in the market to prevent competitors from accessing certain distributors and arenas, (alleging WWE’s exclusivity agreement with Peacock prevents competitors from working with Peacock’s partners, such as Reelz), (alleging Fox and NBC are the two cable networks with the largest coverage in the United States, so that WWE’s exclusivity provisions prevent competitors from accessing a wider audience), WWE caused at least two arenas to reject or cancel bookings by competitors other than MLW).

These barriers, as alleged, are plausible “additional long-run costs that were not incurred by incumbent firms” and that “deter entry while permitting incumbent firms to earn monopoly returns.” Rebel Oil Co.,The factual existence of these barriers, which WWE challengesm is not a question to be resolved at the motion to dismiss stage. Accordingly, the Court finds that MLW has sufficiently alleged circumstantial evidence of WWE’s monopoly power. It need not and does not address the parties’ arguments regarding direct evidence of monopoly power. And since the possession of monopoly power is a greater showing than a dangerous probability of obtaining monopoly power, MLW’s monopoly power allegations are sufficient for both of its claims under Section 2 of the Sherman Act.

“The Court finds that MLW has sufficiently pleaded circumstantial evidence of WWE’s monopoly power. The FAC alleges that WWE captures 92% of the revenue generated by the sale of media rights for professional wrestling programming. Defendant argues that MLW must allege facts explaining why revenue share is an appropriate measurement of market share, but cites only to cases that evaluated the proper market share metric based on factual findings.

At the pleading stage, MLW’s allegations of the revenues generated from the sale of professional wrestling media rights, and WWE’s 92% share of that revenue (with the next largest competitor possessing a 6% share) are sufficient to show dominance in the market.

In addition to defining the relevant market and alleging WWE’s dominance in that market, MLW has also sufficiently alleged barriers to entry, as required to show circumstantial evidence of market power. Plaintiff alleges that WWE has used its dominant stature in the market to prevent competitors from accessing certain distributors and arenas, (alleging WWE’s exclusivity agreement with Peacock prevents competitors from working with Peacock’s partners, such as Reelz), (alleging Fox and NBC are the two cable networks with the largest coverage in the United States, so that WWE’s exclusivity provisions prevent competitors from accessing a wider audience), WWE caused at least two arenas to reject or cancel bookings by competitors other than MLW).

These barriers, as alleged, are plausible “additional long-run costs that were not incurred by incumbent firms” and that “deter entry while permitting incumbent firms to earn monopoly returns.” Rebel Oil Co.,The factual existence of these barriers, which WWE challengesm is not a question to be resolved at the motion to dismiss stage. Accordingly, the Court finds that MLW has sufficiently alleged circumstantial evidence of WWE’s monopoly power. It need not and does not address the parties’ arguments regarding direct evidence of monopoly power. And since the possession of monopoly power is a greater showing than a dangerous probability of obtaining monopoly power, MLW’s monopoly power allegations are sufficient for both of its claims under Section 2 of the Sherman Act.

Booker T Responds to Swerve Strickland’s Post-Show Speech After AEW’s Dynasty 2025 Event

Booker T Responds to Swerve Strickland’s Post-Show Speech After AEW’s Dynasty 2025 Event WWE SmackDown Notes: Rey Fenix Makes WWE Debut, CM Punk Reveals Favor Owed is Paul Heyman to Be In His Corner at WrestleMania 41, New Mystery Vignette Airs, MCMG Wins Shot at WWE Tag Team Titles, Kevin Owens Announces Neck Injury, 4/11 Show Card

WWE SmackDown Notes: Rey Fenix Makes WWE Debut, CM Punk Reveals Favor Owed is Paul Heyman to Be In His Corner at WrestleMania 41, New Mystery Vignette Airs, MCMG Wins Shot at WWE Tag Team Titles, Kevin Owens Announces Neck Injury, 4/11 Show Card Drew McIntyre vs. Damian Priest Made Official for WWE WrestleMania 41

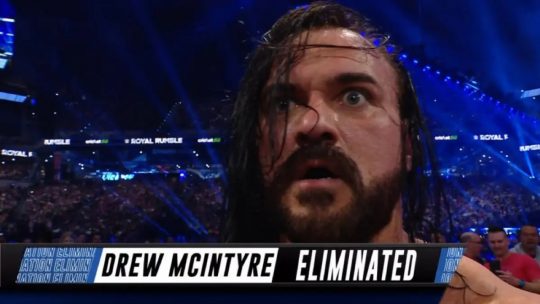

Drew McIntyre vs. Damian Priest Made Official for WWE WrestleMania 41